Book Review

The Artist as Divine Symbol

Chesterton’s Theological Aesthetic

Cascade Books Eugene Oregon

(KALOS) Paperback 2023

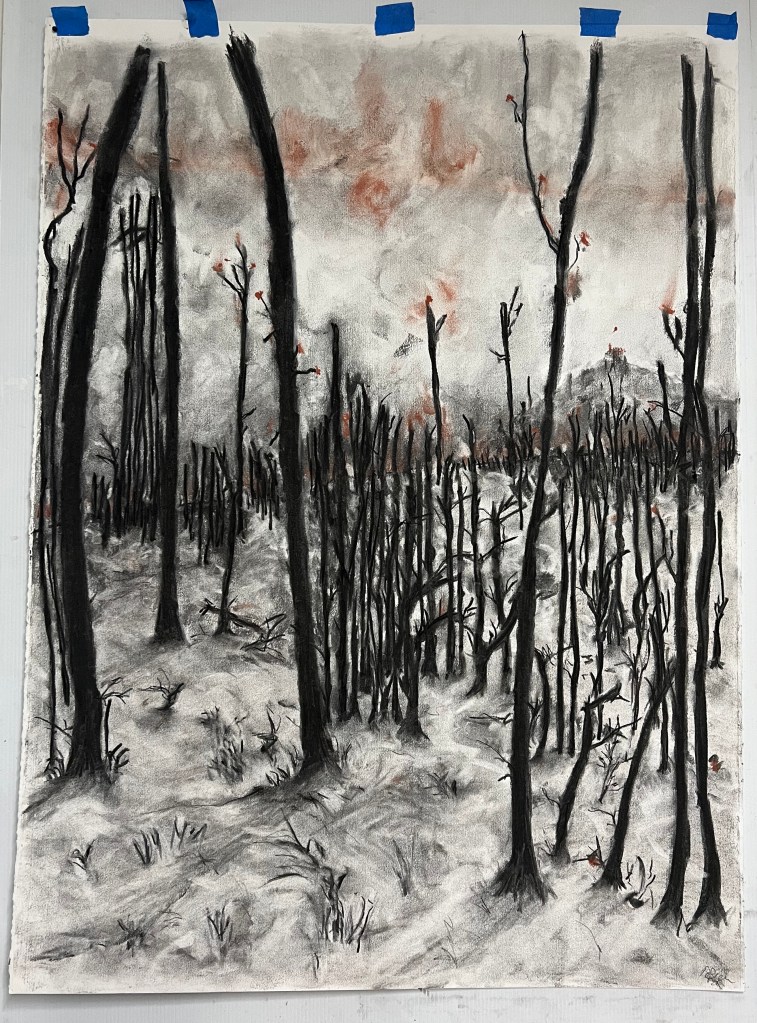

#untitled Charcoal and pencil on arches paper Peter Breen 2024

Review

Peter Breen MA, BTh, ARMIT

Brisbane, Australia.

July, 2024

In 1998 during my second pastoral tenure with a Wesleyan Methodist Church in suburban Brisbane [Queensland, Australia] I attended a series of workshops over two weeks in Melbourne. It was sponsored by Scripture Union [Victoria] World Vision [ Australia] and Whitely College [ Baptist]. It was held at the Carlton Baptist church in an old two story disused shop complex and hosted by New Zealand art lovers and Baptist theologians Mike Riddell[i] and Mark Pierson. The basic idea of the seminar was to consider how to think about and be active around evangelism and worship “using the arts” in the emerging culture. As a pastor in an evangelical organisation at the time, applications and future options were conceived while the arts, my true love, were firing mystery and dreams.

Now the landscape was completely different then – no 9/11, high octane social media, COVID, Trump, Morrison, Putin, Boris or Ukraine/Russian, Palestinian/Israeli atrocities. Almost a generation on and now we are living in an unimagined landscape. However, those of us in that building were thinking then about “new music and art” in worship settings and conversations with “outsiders” that were not based around “selling the gospel.” In 1998 “Church Growth” had become a disease of franchised McDonald’s proportions burning out pastors who were not inclined to be into sales.

Those two weeks opened new doors onto new rooms of thought and imagination, rooms that would lead me to become immersed in the arts, leave the religion based pastoral enclave and return to Medical Imaging [ Radiography]. It would also find me grappling with the arts, fund raising, personal art practice and questioning my theology more deeply as I attempted to unravel and move out from under the iron clad Christian dualism construct. And now I wonder how my path would have unfolded if Adam Carnehl’s book had been written in 1998. But it wasn’t and I am glad to have had the last 22 years to prepare for it.

I found this to be an interesting, insightful and well researched book and an iteration of Adam’s doctoral research at the University of Glasgow. His research credentials for this book series are evident in the 4-page Bibliography and 2 pages of Page Indices. It is one of the Kalos series whose purpose is “…to seek to provide intelligent-yet-accessible volumes that have the innocence of beauty and of true adventure, and in so doing remind us all again of that which we took for granted most of all thought itself. “The book fulfils the parameters – it is “intelligent-yet-accessible” and explores “the innocence of beauty and true adventure….and…thought itself.” As the late Bishop Bruce Wilson notes in “Reasons of the Heart” [ Allen & Unwin 1998] we will – and need to – eventually move from naïve love to a more aware and open eyed love at some point in our lives and so even though beauty perceived has its own innocence it cannot be taken to mean that it necessarily needs to remain so as that late Irish poet John O’Donohue writes in “Beauty – The invisible embrace” [ Harper Perennial 2003] I am not suggesting in questioning the “innocence of beauty” that beauty is complicated but that it has multiple facets, facets which will arrest our souls if we stay with each facet with intention and time and learn as O’Donohue says at least the difference between beauty and glamour. Adam seems to be have been captured by some of the facets of beauty and is not conversely held by the simplistic views of Ruskin’s photorealistic approach to painting clouds being the only beauty representation that pleases God.

My “thinking life” before pastoral appointments and during them included applied science and theology and an immersion in a range of social and theological constructs that had not honoured the arts or open ended question thought processes. At times I thought they had but they had not. My whole world of thought at its deepest levels were that of a passionate insistence on dualistic evangelical conversion and subsequent piety. The bottom line had always been to find ways to “get people saved and sanctified” aka Billy Graham and use love of “the other” if necessary. The arts were, in that context, only utilitarian, that is, for worship or evangelism. In some ways that agenda of the Christian church seems to have hardly changed, particularly in the narrow evangelical fundamentalism that I left. I am thankful that in the midst of growing up in a fundamentalist household my Christian parents had oddly enough fostered a love of a wide ranging arts exploration in their children – except for the devil’s “rock and roll music” – that served us well and that partly saved us from a more cultic infirmary.

Adam seems, within a commitment to the Kalos series principles, to have what has become a recurring theme in some writing by Christian authors – a need to convince himself and his readers to consider art deficient if it does not “symbolise” the mark of the creator clearly in the making and being of art by the artist. The “artist is a symbol of the divine”. In so doing it places it for me in a dualistic monotheistic construct. I suspect that as a Lutheran pastor this would be the bottom line of his world view. He is not, however, advocating a smarmy sentimentality or icon-only art. He is not advocating biblical texts on the back – or hidden in the painting – of the canvases or explanations in the artist statements that are tantamount to gospel presentations. It does seem to be more nuanced.

His reasoned approach in this book considers each [male] artist and artist’s output with thoroughness – John Ruskin, Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde and GK Chesterton. His highpoint, as the title suggests, is the art critic and novelist G K Chesterton. It was this book and this kind of research that I needed when, as a pastor after the above mentioned seminar in Melbourne, I launched a regular art event[ii] as part of local church life. Being a non-conformist denomination and one that eschewed art – unless it was at least if nothing else, “appealing” and utilitarian – made for some convincing times. The experiment on church property lasted 2 years as a bi-monthly non-evangelistic-non-worship-art-for-arts-sake event. That denomination in general was icon free – apart from the standard symbolic empty cross – not crucifix – and communion table.

In respect of this book’s overall theme the dust cover critiques are enlightening:

“In this densely written and learned study of nineteenth-century and fin de siecle aesthetics, Adam Carnehl recovers Chesterton as an important figure in theological mysticism after Ruskin, Pater, and Wilde. Rooted in German idealism and Romantic thought in Blake and Coleridge, this book deftly re-evaluates Victorian aesthetics culminating in Chesterton, in the recovery of the imago dei, and in God as divine artist.” David Jasper. University of Glasgow.

“By contextualising Chesterton’s intellectual beginnings in later Victorian aesthetics, Adam Carnehl reveals the deep roots of his subject’s theological vision and that vision’s ultimate coherence. At a time when theology is again turning to the arts, Carnehl is able to show that Chesterton remains a resource for serious theological reflection, over and above the sometimes polemical apologetics of his later years. Admirably clear, The Artist as Divine Symbol fills an important gap in the literature.

George Pattison. University of Glasgow.

My time post-pastorate since 2003 has been immersed in the arts, medical imaging, family life and completing an MA in Creative Arts Therapies. And I have been learning to see as per John Berger in “Ways of Seeing. “

“Berger challenges the elitist and mystified status of art that neglected the political, social, and ideological aspects that shaped the ways in which we look at art. “ [Google Search]

And I’ve been exploring Kandinsky’s philosophy “At its outset all art is sacred and its sole concern is the supernatural. This means that art is concerned with life – not with the visible but the invisible.” [ Quoted in “Zero at the Bone – Fifty Entries Against Despair” Christian Wiman. Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2023]

A book I have found of immense insight after happening to read a review by Rex Butler in an Art Forum magazine is “No Idols: The Missing Theology of Art – Power Polemics” [Thomas Crow, Power Publications 2017.] The approach to “the missing theology of art” by Thomas Crow needs to be read with Carnehl’s book as it could be argued that they share vague similar foundational frameworks. “Art is probably the last remnant of magic we have left, because we’ve jettisoned most of the magical beliefs that used to guide human behaviour and perception of the world. But in getting rid of all those things we left ourselves with almost no connection to the unknown” From the cover Thomas Crow, Radio New Zealand October 2016.

“Arts of Wonder – Enchanting Secularity – Walter De Maria, Diller and Sofidio, James Turrell, Andy Goldsworthy” [Jeffrey L. Kosky, University of Chicago Press, 2013] crosses over with Crow’s appraisal of James Turrell in No Idols who was raised as a Quaker and as such subscribed to “…the Christian sect that best stands for resistance to idolatrous vanities and their factious consolations…that is, art” In a review of Crow’s book Graham Howes reviews “there are many ways of mapping a religious sensibility in art, and not all of them entail overt iconography’ … what Crow calls his ‘paradoxical project… the discovery of valid religious representation in visual art after virtually defining it out of existence’ (p. 108) unfolds with an enviable mixture of art historical precision, theological awareness, and evident empathy for each artist. If relatively little attention is paid to any broader cultural canvas, each artist is vividly portrayed as homo religiosus in their own right.”

Carnehl’s evaluation of each artist takes a circular route from Ruskin’s remarkable approach to what God’s own art should be – that is, perfectly resolved clouds – through the reactionary push back art for art’s sake movement of Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde who though not anti-religion or anti-god could “see through” Ruskin’s construct. He completes the circle at G K Chesterton of course while referencing Chesterton being enamoured with William Blake, Coleridge and the romantics. Chesterton sees the limits of Ruskin but he moves on from the Pater/Wilde reactionary position. Carnehl posits Chesterton as a significant art critic and lay theologian, a voice to be rediscovered “…at a time when theology is again turning to the arts …” and whose focus is to capture the idea of Ruskin, filter it through Blake and Coleridge with a nod to the reactions of Pater and Wilde. The profile of Chesterton however seems to be as a thorough going dualist either approving or disapproving of artists and art as media for the creator to be known through and as energising the artist who would eventually acknowledge it. It would be interesting to read more of Chesterton’s later life as he apparently developed a more polemic style in his art criticism.

Recommendation:

I recommend The Artist as Divine Symbol as an important addition to artists reading lists and for artists of all spiritual/religious persuasions. Art, according to Kandinsky, is primarily a spiritual venture not a decorative one*. I see it more broadly than Kandinsky as per, for example, John Berger’s Ways of Seeing but I certainly agree with Kandinsky that art is more than decoration and design. Within the current Christian religious construct homilies and sermons are an art performance with hints of poetic brilliance although in many quarters, for example in Church Growth and Triumphalist paradigms, they have largely become a series of sales pitches and coaching classes.

It would be helpful if The Artist as Divine Symbol was added to Theology 101 at pastoral training institutions who also need to develop a theology of art and creativity along with

- No Idols: The Missing Theology of Art Power Polemics Thomas Crow, Power Publications, 2017

- Arts of Wonder Jeffrey L Kosky, University of Chicago Press, 2016

- Emergence Magazine – Ecology, Culture and Spirituality, Editions 1 – 5

- Reasons of the Heart Bruce Wilson, Allen & Unwin, 1998

- Beauty – The Invisible Embrace John O’Donohue, Harper/Perennial, 2003

- Imagination in an Age of Crisis – Soundings from the Arts and Theology Edited by Jason Goroncy & Rod Pattenden, Pickwick Publications Wipf & Stock Publishers 2022

[i] Rev Mike Riddell died in his sleep in 2022 in Dunedin, NZ. He was 69.

[ii] Café Jugglers was launched in October 1998 with one of my sons and two other friends. Another of my sons headed up what become known as Jugglers Art Space Inc for the first 7 years [ I assumed that role in 2011] after we took Jugglers to the streets in 2002 and bought a building in the inner city of Brisbane. Jugglers grew to be a vibrant arts hub in Brisbane from 2002-2018 when we sold it to the local YMCA. We are currently working on a monograph reflection of our venture. www.jugglersartspace.com.au

*Art, if one reflects on it and makes an exception of the Greeks, has only rarely been concerned with external reality. The world becomes the aim of an activity that ceases to be creative and lapses into representation and imitation only after its initial theme and true interest has been lost. The initial them of art and its true interest is life. At its outset, all art is sacred and its sole concern is the supernatural. This means that it is concerned with life –not with the visible but the invisible. Why is life sacred? Because we experience it within ourselves as something we have neither posited nor willed, as something that passes through us without ourselves as its cause – we can only be and do anything whatsoever because we are carried by it. This passivity of life to itself is our pathetic subjectivity – this is the invisible, abstract content of eternal art and painting.

P21 Zero at the Bone – Fifty Entries against Despair Christian Wiman, Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2024

Thanks:

- To WIPF for inviting me to write a review of The Artist as Divine Symbol in exchange for the book.

- To the late John Uren of Scripture Union Victoria for inviting me to the seminar in Melbourne in March 1998.

- To Rev Mark Pierson and the late Rev Mike Riddell for saying stuff, making suggestions and opening doors that landed me in a new and unfolding world of wonder.

Well done Peter. The personal experience you draw on in understanding your orientation to art is important, and greta to read.

On a critical note, the claims that art is exclusively spiritual, mysterious and so on , does not fit well with the materialist view, a la John Berger (Ways of Seeing). For Berget, art is intended to comment on and reflect the artist’s preferences in representing the world. In this sense “representation” is intended to offer a contradiction to what is constructed as the world we see outside of art, where the representation “pushes” the viewer to re-orient themselves to the world by responding to the contradiction – the Hegelian/Marxist method. Ergo, material change can emerge from the new consciousness the art generates.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much Marcus for this review of my review! I drew a long bow in setting the review within a very autobiographical experience based context and in that sense it was less review. But the book spoke to those deep seated constructs we are both familiar with and that I needed to continue to unpack as I have done via MIECAT and some of my drawings. Your comments on Berger were very helpful and I will read him again with new understanding. It seems that there’s a host of lenses that artists have used and that have evolved eg Kandinsky to both “see” and imbed in their practice. Rothko is another.

LikeLike